Utica’s Olmsted Trail

When heading across Upstate New York’s east-west corridor by car, bike, or boat, consider stopping in Utica, a small “Olmsted City” with an outsized architectural heritage—in addition to an array of marvelous restaurants and one of the finest art museums in the country.

"To conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and the wild life therein and to provide for the enjoyment of the same in such manner and by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations."

Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., National Park Service Organic Act (1916)

Utica is a town of 62,000 people on which Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., the preeminent landscape architect of the first half of the twentieth century, left an unusually large and impressive mark: a sprawling park and parkway system and nearly a half dozen neighborhoods laid out under his personal supervision by his firm, Olmsted Brothers of Brookline, Massachusetts.

Utica is also home to an impressive collection of structures and artistic works created by Olmsted’s peers—contemporaries who were also widely considered leading people in their fields in the period between 1900 and 1930, and left behind more famous works in New York City and Washington, D.C. These sites from Utica’s heyday as an important textile center made it something much more than a typical mill town.

As a premier landscape architect, environmental planner, educator and conservationist, Frederick Law Olmsted Jr.'s accomplishments spanned the country and made an indelible mark in the realm of American city planning, including

~Landscape for the White House, National Cathedral, National Mall, Federal Triangle, and Jefferson Memorial in Washington, DC;

~Founder of Harvard’s Landscape Architecture program;

~Work on the design of several National Parks including Everglades, Yosemite, Acadia, and Redwood

Olmsted, Jr. also created planned neighborhoods like Forest Hills Gardens in Queens (New York City), as well as Utica’s Ridgewood, Proctor Boulevard, Sherman Gardens, and Talcott Road neighborhoods.

Utica, NY

The Olmsted Trail consists of two interlocking corridors that are easily accessible from the Thruway and the Empire State Trail, and since Utica is not a very large city, the entire trail covers only 8 miles—traversing a few or even all of the four suggested itineraries will not require too much of your time. Together they tell the story of a prosperous and proud little industrial city in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century that was home to civic-minded patrons.

However, Utica’s past wasn’t simply the work of well-heeled local patricians. Immigrants also played a key role in building Utica and making it a distinctive place. In the early nineteenth century, immigrants from Ireland, Germany, and Wales powerfully influenced the development of the local culture and culture. In Utica’s Olmsted Era (1900-1930), immigrants from southern and eastern Europe—predominantly Italians and Poles—provided the labor that made Utica’s past industrial success possible.

The traces of their cultural heritage, along with the physical heritage Olmsted and his contemporaries left behind, link Utica’s past and present. Today’s immigrants, very largely comprised of refugees, constitute another such link to that past, in that their contributions are helping to preserve Utica’s physical heritage, contribute to its economy, and further enrich a distinctive local culture.

Together, all these aspects of Utica’s past and present make it a place worth visiting and an interesting and rewarding place to live.

Accessing The Trail

The Olmsted Trail is located on (or immediately adjacent) to two intersecting streets: Genesee Street and the Parkway. Coming from the east or west, you can easily access Genesee Street from the New York State Thurway or the Empire State Trail. When approaching by bike on the Empire State Trail from the east, you can easily enter access the Olmsted trail by heading southward onto Dyke Road in Schuyler, follow bridges over the New York State Thruway and the Mohawk River, head right (or west) on Bleecker Street, and then left (or south) onto Culver Avenue, which will bring you to the first of Utica’s Olmsted parks—F.T. Proctor Park—and Utica’s beautiful Olmsted-designed Parkway. If you opt to come in by bike from the East, we would suggest using Itinerary 2 as your first guide into the city.

Intro to 19th & 20th Century Utica

Utica and the surrounding communities of southeastern Oneida County were the first major settlements on the frontier after the American Revolution. The British had banned settlement to the west of what is now the Utica-Rome metropolitan area, and after their departure in 1783, the area became a magnet for settlers from New England in the first great post-Revolutionary land rush.

Oneida County became the second most populous county in New York, the most populous state—the “Empire State”—in the opening decades of the nineteenth century, and Utica, the county’s largest municipality, became one of the most prosperous and best-known communities in the country.

Oneida County was for decades the leading producer in New York State of a wide array of industrial and agricultural products, and Utica, the nearby city of Rome, and their environs comprised the industrial core of the county. For decades, Utica was justifiably considered a progressive little city characterized by industrial and cultural vitality, and it bred a class of national-caliber business and political leaders.

Robber Barons and Philanthropists

“THE PUBLIC BE DAMNED!” Those four words, uttered by railroad tycoon William Vanderbilt in 1882, said much about Gilded Age America—a time when fortunes unprecedented in American history were made, and the imbalance of wealth led to an imbalance of power that alarmed many Americans.

However, in the Gilded Age, and in the Progressive Era that followed it, other people of wealth and position sought to use their wealth to benefit society, as well as themselves. Such people built enduring institutions like libraries, museums, parks, schools, churches, and other amenities. Their objective was to enhance the quality of life and civic pride among average people. Many of these wealthy philanthropists were motivated by a belief that urban societies needed to be places of refuge and enlightenment as much as they were places where wealth was made and enjoyed.

Two such figures were Thomas R. Proctor (1844-1920) and his wife, Maria Watson Williams (1853-1935). Their name, Proctor, is found all over Utica, and they did much to create what we call the Olmsted Trail. In short, the local public in Utica was blessed—not damned—by some of its wealthiest citizens and local businesses in the city.

Transportation

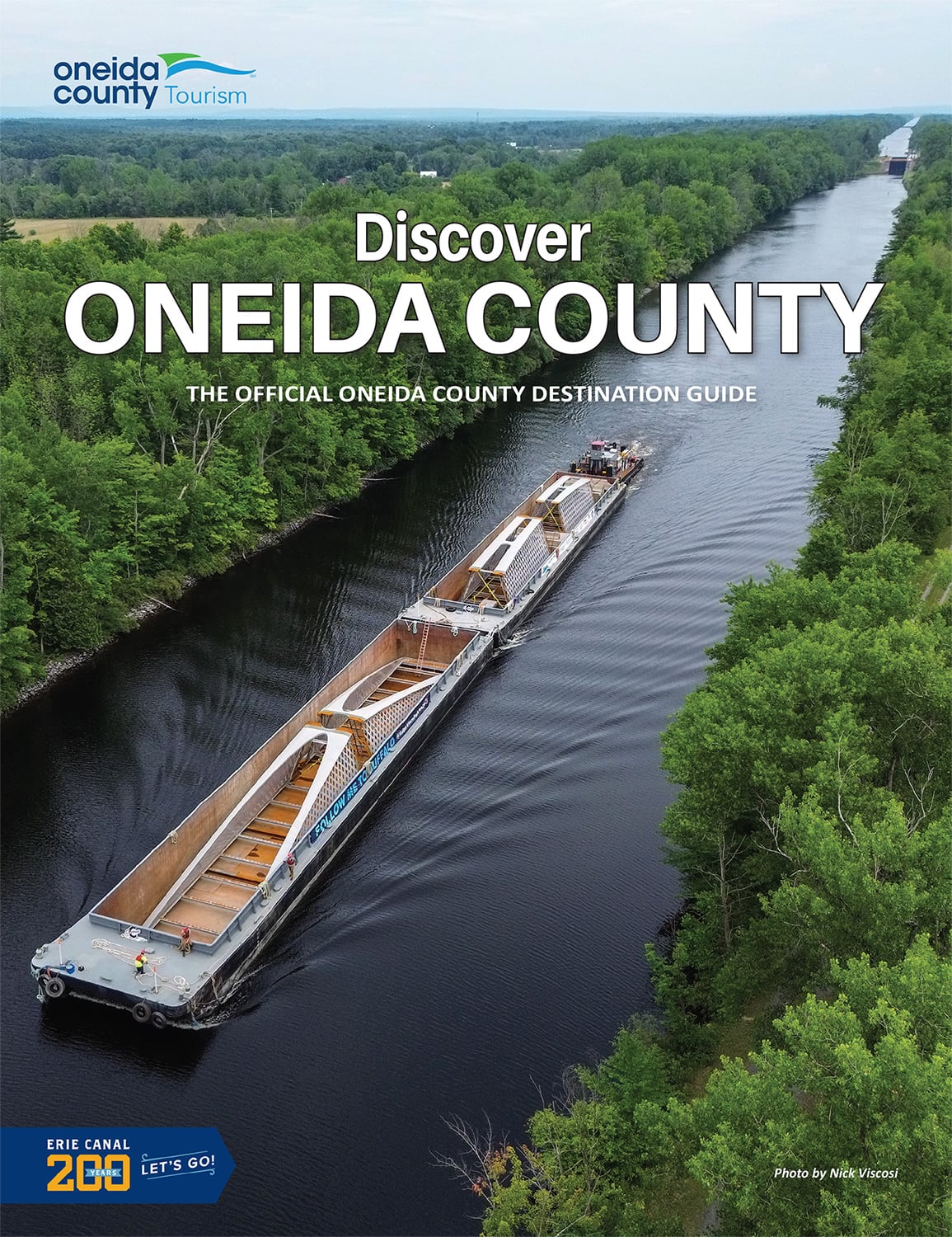

Utica played an important role in the formative years of American industrialization, notably in the fields of transportation and communications. Utica’s stagecoach operators made their mark nationally, established Utica as a stopping point for westward coach traffic, and played a key role in the creation of the American Express Company [LINK to “Communications” section]. In addition, the first stretch of the Erie Canal, which ushered in the next great transportation revolution and catalyzed America’s astonishing growth in the nineteenth century, was opened between Utica and nearby Rome in 1819.

As transportation technology changed, Utica kept up with the times. The Utica and Schenectady Railroad was one of the longest in the country when it opened in 1836, and for many years it was the longest in the state. In the 1860s, the Utica and Schenectady was absorbed by the New York Central Railroad, which later built Utica’s palatial railroad station [LINK]. When the railroads sped more and more people past Utica, depriving the city of its previous role as a rest stop, the city found new purpose in textile manufacturing.

Utica also had important early connections to the transportation technology that would dominate much of the twentieth century and beyond: the automobile. It was the home of a number of early automobile manufacturers in those days before Detroit became the undisputed center of the industry. The most successful was the Willoughby Company (1899-1939). At its height in the mid-1920s, Willoughby built approximately 500 custom bodies annually for a number of manufacturers, including Lincoln, Cadillac, Rolls Royce, and Duesenberg; the company also manufactured auto bodies for the Rockefellers, Al Capone, boxer Joe Lewis, and Presidents Coolidge and Hoover.

Charles Stewart Mott (1875-1973) was a wheel and axel manufacturer in Utica who moved to Detroit and became one of the two principal founders of General Motors in 1908; Mott was for many years GM’s president and its single-largest stockholder. He also represented the Utica Automobile Club (founded in 1901) at a meeting in Chicago in 1902 with three other such organizations that created the American Automobile Association (AAA). In addition, the famous 1908 New York to Paris automobile race, the first of its kind, passed through Utica.

To accommodate the growing use of the automobile, and to bring more people into Utica’s new park system, Thomas R. Proctor, local officials, and Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., developed a plan in 1910 to extend Utica’s scenic Parkway eastward from Elm Street, eventually expanding it nearly seven-fold. In so doing, they carefully picked a route along Roscoe Conkling Park that ensured the best views of Utica and the Mohawk Valley. Later local accommodations to the automobile were far less successful. However, Utica’s beautiful Parkway escaped the fate of Buffalo’s Humboldt Parkway, which was destroyed in the post-World War II rush to create cross-town expressways supposedly to make cities more functional and livable.

Communications

Samuel F.B. Morse, the father of modern telegraphy (the first precursor to internet communications), married a woman from Utica, often visited the city, and partnered with a group of Uticans in an early effort to launch a commercial enterprise based on his technical achievements. Indeed, James Reid, the early historian of the telegraph, wrote that the new technology “found no friends in Manhattan” and that it was left “to the inland cities of Rochester and Utica to…rear it to national greatness.”

Utica stagecoach operators Theodore Faxton and John Butterfield and other investors founded what became known as the New York, Albany, and Buffalo Telegraph Company, one of the world’s first telecommunications companies, in Utica in July 1845. Faxton served as president of the company and Samuel F. B. Morse served on its board of directors, as did Butterfield; one of the largest telegraph companies in the US, it was absorbed by the Western Union Company (the Google of its day) in 1864. Butterfield also ran a stagecoach line that was responsible for carrying the US Mail and passengers west of St. Louis before the building of the transcontinental railroad, and in 1850 he created the American Express Company in collaboration with two men named Henry Wells and William Fargo.

Several local newspapers achieved national stature in Utica’s Olmsted Era. Most notable was the weekly Saturday Globe (1885-1924), the first newspaper in the United States to use halftone photographic reproduction. With 300,000 subscribers coast-to-coast (which it built through pioneering use of regional editions) and abroad, it counted even Queen Victoria among its subscribers. The Utica Morning Herald (1857-1900), another newspaper of national stature, was edited by Ellis Roberts, who later served as Assistant Treasurer of the United States (1889-93) and Treasurer of the United States (1897-1905).

Textile Industry

In 1845 the citizens of Utica commissioned one of the first industrial studies carried out by an American community, and it inspired local investment in steam-powered cotton and woolen goods manufacturing. Utica consequently became one of the country’s leading centers of textile and garment manufacturing, mostly cotton sheets and woolen underwear. Some 25,000 people were employed in the industry locally at the height of the Olmsted period, when Utica’s population was 90,000.

The mills at first employed German and Irish immigrants, as well as migrants from the rural areas around Utica. By the early twentieth century, the mills were increasingly dominated by southern Italian and Polish immigrants. Italians also constituted the backbone of the local garment industry.

The local textile-based economy hit its peak between 1890 and 1920—precisely when Olmsted was most active in Utica—at which point manufacturers slowly started moving operations to the American South. The impact of this trend was not fully recognized until after World War II, when the biggest textile mills departed. Although some Uticans had questioned the area’s heavy dependence on a single industry as early as the late nineteenth century, most were content to rely on it for local prosperity. Valuable time was therefore lost in the decades leading up to 1945 that might have been used to position the city for a different economic future.

Politics

With a prosperous local economy in the nineteenth century and the prominence that came from being an early center of western population growth, Utica became a breeding ground for political leadership.

Horatio Seymour (1810-1886), was mayor of Utica and Governor of New York (1853-54, 1863-64). The Democratic Party tried to recruit him to be their presidential nominee several times over the course of his life, but 1868 was the only time he conceded. He refused to be renominated as governor in 1876 and 1879, and when he was called upon to serve in the US Senate in 1876, he suggested another Utica Democrat, former congressman Francis Kernan (1816-92), who was subsequently elected.

In 1875-81, Kernan and his fellow Utican, Roscoe Conkling (1829-88), simultaneously occupied both of New York’s seats in the United States Senate. Conkling served as Oneida County district attorney and mayor of Utica before turning 30, followed by nearly a decade in the US House of Representatives. He then served in the US Senate for 14 years and was the first person from New York to be appointed to a third term as a US Senator. As senator, he became the boss of the powerful New York State Republican machine. The Republican Conkling and the Democrat Horatio Seymour were brothers-in-law—and there was no love lost between them, and Conkling campaigned vigorously against Seymour’s presidential bid in 1868. Conkling was as much worshiped by his supporters as he was despised by his opponents; he destroyed his political career by resigning from the Senate in 1881 amidst a dispute with President Garfield over patronage.

James Schoolcraft Sherman (1855-1912), a one-time mayor of Utica and prominent member of Congress, served as the Vice President of the United States in the administration of William Howard Taft (1908-12). Known popularly as “Sunny Jim,” Sherman was a well-liked, jovial man who nevertheless clashed bitterly and unsuccessfully with Theodore Roosevelt in 1910 over political reform. Sherman died in office, in 1912, but not before he became the first Republican to be re-nominated to the vice presidency. President Taft and members of the Supreme Court and Congress attended his funeral in Utica in October 1912.

The Proctors

Thomas & Maria

Thomas

Thomas Redfield Proctor (1844-1920) was born in Proctorsville, Vermont—and the very name of the place tells a story, as he was born into an enterprising New England family with a strong history of public service. His hometown was named for his great grandfather, an officer in the Revolutionary War. Thomas’ cousin, Redfield Proctor, was governor of Vermont, secretary of War, and a United States Senator who had his own town named for him—Proctor, Vermont—where Redfield founded the Vermont Marble Company.

Thomas served in the Union Navy in the Civil War as secretary to the admiral in command of the Pacific Squadron, and after he was discharged, he briefly managed family business interests before buying his first hotel, the Tappan Zee House in Nyack, New York.

In 1869, he moved to Utica, and at the age of 25, he bought Bagg’s Hotel, the most historic local hostelry, which counted among its guests the Marquis de Lafayette, Joseph Bonaparte, Aaron Burr, Henry Clay, Washington Irving, Charles Dickens, General William Tecumseh Sherman, and presidents James Garfield, Chester Arthur, and Grover Cleveland. In 1879 he purchased another large local hotel, the Butterfield House, as well as a hotel in Richfield Springs, New York, a fashionable spa town about 25 miles from Utica. He also invested in a number of other business enterprises, including banking, textiles, and a progressive local newspaper, the Utica Daily Press.

Maria

Maria Watson Williams Proctor (1853-1935) was a woman of considerable means in her own right. Her maternal grandfather, Alfred Munson, made a string of highly successful investments in canals, railroads, textiles, mines, real estate and other endeavors. Her father, James Watson Williams, was a successful lawyer, investor, and mayor of Utica; he commissioned the eminent American architect Richard Upjohn to design both the family’s parish, Grace Episcopal Church, and the city’s longtime city hall, across from one another on Genesee Street, Utica’s principal thoroughfare.

Maria’s mother, Elizabeth Munson Williams, proved to be a canny investor who increased the family fortune and then plowed it into sound conservative investments—the New York Times reported at her death that Elizabeth supposedly held more US treasury notes than any woman in the world. Elizabeth had a taste for fine art and philanthropy, and her acquisitions formed the core of the family’s impressive art collection.

Her daughter Maria consequently occupied a unique place in local social and political life, and not just (or principally) because she was married to a prosperous man like Thomas R. Proctor. When there was talk in the early 1930s, well after Thomas’ death, of replacing the Upjohn city hall her father had commissioned, Maria’s public objections stopped the discussion in its tracks (unfortunately, old city hall fell victim to Urban Renewal in 1968). In the depths of the Depression, Maria deposited $1,000,000 in local banks (nearly $19,000,000 in today’s money), thus heading off a local bank panic; during the same year, she paid to have Utica's historic Bagg’s Hotel razed by hand, brick by brick, so as to maximize the amount workmen could earn from the job in those economically troubled times.

Local Benefactors

Thomas and Maria made Utica traveled extensively in the US and abroad and made friends far and wide. Thomas was a member of the Metropolitan Club and other social clubs in Manhattan, as well as the influential Adirondack League. He was also prominent in Republican politics in New York State and served as a delegate to the Republican National Conventions of 1908, 1916, and 1920. President Taft appointed him to the board of visitors at the US Naval Academy at Annapolis—and as a former president, Taft paid the Proctors a visit and had lunch at their home in 1918.

Thomas and Maria also had a keen interest in the arts. They endowed the Thomas R. Proctor Prize for sculpture and portraiture that is still conferred at the National Academy of Design. More locally, and significantly, in 1919 they earmarked the bulk of their fortune to the creation of a school of art and museum which came into being as the Munson Williams Proctor Arts Institute (MWPAI) after Maria’s death in 1935.

The Proctors also donated land for Utica’s elegant public library building, designed by the celebrated New York architectural firm of Carrère and Hasting, and they were generous patrons of Grace Church. Maria and her sister Rachel also commissioned the noted American architect Richard Morris Hunt to design a memorial to the Munson and Williams families that for generations served as the home to the Oneida County History Center in Utica (like the old city hall, it fell victim to Urban Renewal).

Apart from the creation and endowment of MWPAI, their most visible gift to their hometown was the donation of approximately 600 acres of park land. In the late 1890s, Thomas R. Proctor began articulating a vision for a vastly expanded system of public parks connected by a broad, grass-covered, tree-lined boulevard. Dissatisfied by insufficient support among leading local citizens, Proctor took matters into his own hands by acquiring land and hiring the leading landscape architect in the country, Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., to transform that property into public parks. While working privately for Proctor, Olmsted was also commissioned by Proctor’s allies in the Utica Chamber of Commerce to do a comprehensive report on Utica, published in 1908, that is among a handful of such studies Olmsted carried out nationally.

The bulk of the Proctor donation consisted of 370 acres that became known as Roscoe Conkling Park. Two smaller parks, F.T. Proctor and T.R. Proctor, are located at the east end of the system. All of this land—nearly 600 acres—was developed into public parks by Olmsted at Proctor’s expense, and Proctor was actively involved in the development of these parks. Between 1908 and 1919, the City of Utica built the Parkway, also designed by Olmsted, to connect these three parks. Local residents were so grateful that they began in 1916 to hold an annual celebration known as Proctor Day and continued to do so until 1942.

Other locally wealthy individuals, as well as local businesses and other institutions, emulated the Proctor example by making lasting contributions to the local landscape, often hiring, as did the Proctors, the leading American architects and artists of the era to execute their projects—and Utica therefore is home to works that share paternity with such better-known landmarks as Grand Central Station, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, the Waldorf Astoria Hotel, and St. John Divine Cathedral.

The Olmsteds

A Father & Son Legacy

The Father

Utica’s park and parkway system (which comprises approximately 80% of the city’s public parkland) was designed by Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr. (1870-1957), between 1905 and 1919. Olmsted also designed neighborhoods adjacent and near to this park system and in the nearby village of New Hartford between 1913 and 1930.

Olmsted’s father, Frederick Law Olmsted, Sr. (1822-1903), co-designed Central Park in Manhattan with Calvert Vaux in 1858-62. Olmsted, Sr., went on to design or co-design Brooklyn’s Prospect Park, Boston’s Emerald Necklace park system, America’s first park and parkway systems in Buffalo and Louisville, and parks in Chicago, Rochester, and many other American communities, in addition to Mount Royal Park in Montreal. He also devised the landscape designs for the Biltmore Estate in Ashville, North Carolina, and the famous Columbian Exposition of 1893 known as the “White City.”

Olmsted, Sr., was a champion of naturalized park design, in contrast to the previously more common, more formal English and French garden styles. Although Olmsted’s style looked naturalized, the final product very much depended on the human hand and often entailed major, if well-camouflaged, alterations to the natural landscape. The Olmsted style became the preeminent model for American urban parks in the nineteenth century, and thanks to the work of his sons, it powerfully shaped the American urban landscape for a century, at least until the retirement of Olmsted, Jr., in 1949.

The Son

Olmsted had two sons, John (1852-1920) and Frederick Law, Jr., and after the retirement of their father in the late 1890s, they created the firm of Olmsted Brothers, based in Brookline, Massachusetts, that carried on the work of their father. John was an accomplished landscape architect, but it was Olmsted, Jr., his father’s namesake, who made the biggest impact.

Olmsted, Jr., devised or played a leading role in designing the landscape for the White House, the National Cathedral, the Jefferson Memorial, and the National Mall. He served on two federal commissions for the better part of two decades that reshaped the part of central Washington, D.C., known as the “Federal Triangle.” He also made significant contributions to a number of national parks, including Everglades, Acadia, and Yosemite (a promontory in the latter park is named in his honor). He helped to preserve California’s giant redwood forests (a grove of these redwoods is named in his honor) and was a driving force behind the creation of the National Park Service in 1916. He taught the first courses in landscape design at Harvard and was a founder of that university’s landscape design program, the world’s oldest and most renowned program of its sort.

Olmsted, Jr., and Urban Planning

Olmsted also carried out urban design studies for a number of cities, including Detroit, Boulder, Pittsburgh, New Haven, Rochester, and Newport. He produced one such study for Utica in 1908 that envisioned ringing much of the city with green space; Utica’s park and parkway system represents a significant realization of that plan, but other aspects of the plan, including an envisioned riverfront park not dissimilar to another of his father’s creations, the Fens in Boston.

Even while working on Utica’s extensive park and parkway system—which covers an area nearly 70% the size of New York’s Central Park—Olmsted took on a series of commissions to lay out a new, suburban-style neighborhoods in Utica: Brookside and Sherman Gardens in upper East Utica, and Proctor Boulevard, Ridgewood, and Talcott Road in South Utica.

Throughout all of these projects, Olmsted relied heavily on later Olmsted Brothers partner Edward C. Whiting (1881-1962). Nevertheless, Olmsted himself came to Utica innumerable times to consult and oversee the work being carried out, and his correspondence with Thomas R. Proctor and City officials in relation to these projects was extensive. Together, these neighborhoods and Utica’s park and parkway system constitute an unusually large Olmsted heritage for such a small city.

Getaway Guide

Attractions

Forks Out, Feet Moving: July Events in Oneida County

Oneida County is heating up this July with two of the summer’s most exciting happenings: Boilermaker weekend and the launch of the first ever Oneida County Restaurant Week. Whether you’re lacing up your sneakers, grabbing a fork, or here to soak up the atmosphere, there’s something for everyone this month. Oneida County Restaurant Week: July… Read more